The topic of homelessness is a hot-button issue in Canada. And while it’s debated between governments and communities, realtors and renters, very real people are experiencing it in real time. Here, we lay out an introductory resource to the topic of homelessness in Canada and Metro Vancouver: who is experiencing homelessness, why, and what we can do to help.

Table of contents

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘homelessness’? It might seem obvious: someone who doesn't have a home. In reality, homelessness isn't so simple.

According to the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, homelessness is the situation of an individual, family, or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate means and ability to acquire it.

For those of us looking to help, we must understand the various circumstances that can lead someone into homelessness.

Here, we take a deep dive into the reasons people experience homelessness. We hope it will equip you with the knowledge necessary to have clearer, more productive responses to the homelessness crisis in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, BC, and beyond.

How many people in Canada and Metro Vancouver are homeless?

All images in this story are re-enactments.

People without homes experience a lack of safety and security that affects all areas of their lives. And the experience of homelessness is on the rise, bringing with it a host of interrelated social and economic challenges.

In Canada, the estimated number of homeless people sits between 150,000 and 300,000.

These numbers already feel substantial, but another eye-opener is that the true number of people without housing could potentially be higher. Numbers that track homelessness come from what is called a Point-in-Time count (PiT), where people self-identify they are homeless at the time of the count. As a result, even if someone appears homeless but they don’t self-identify, they aren’t counted as experiencing homelessness. Point in Time surveys also don’t account for the “hidden homeless”: people who are unhoused and temporarily staying with a friend or family member.

Hidden homelessness also carries a gendered component. Women and their children are more likely to be undercounted: a lack of safe housing for women ends up pushing women into emergency shelters or other services that aren’t designed to meet their needs or recognize them as homeless. Additionally, the lack of adequate safe spaces leaves some women trapped in potentially traumatizing or violent situations of homelessness — where they’re also not counted. Only 13% of emergency shelter spaces across Canada are women-only and 10% are family based, compared to 30% men only and 38% all genders.

To see how much safe housing matters for women, read Laura’s story.

Homelessness also has more layers to it than the number of people who are unhoused. For people experiencing homelessness, their situation is often compounded by poverty, mental health struggles, trauma, and/or struggles with addiction. People experiencing homelessness are often stigmatized for any or all of these complex challenges. It’s important to recognize that the problem of homelessness is both simple and complicated: people need homes. Yet a home is just the beginning.

What causes homelessness?

Homelessness can be caused by a variety of reasons, but the most common causes of homelessness are usually the result of structural factors, poverty, and housing supply.

Structural and systemic factors

Structural factors that can drive someone into homelessness include (but are not limited to) a lack of adequate income, inflation, limited access to affordable housing and health supports, and/or experiences of discrimination. When difficulties begin to intersect, we can understand how holding onto a place to live can become increasingly difficult.

Systems, too, can contribute to homelessness when people fall through the gaps. Newcomers to Canada can struggle with language barriers and unfamiliar processes. Senior citizens are often working to navigate technologies and systems that have changed dramatically during their lifetimes. People’s housing can be disrupted by extended hospital stays and economic downturns. Much of these external forces are outside of our control — and put safe, affordable housing out of reach.

Poverty

Poverty and homelessness are strongly linked, as people who experience poverty struggle with affording necessities like housing, food, childcare, healthcare, and education.

“Poverty can mean a person is one illness, one accident, or one paycheque away from living on the streets.” — The Homeless Hub

Growing poverty rates in BC should raise concern. British Columbia received a D+ grade overall for poverty in Food Banks Canada’s 2023 report card. The unaffordable cost of living in British Columbia plays a key role: people living in poverty spend 54% of their earnings on fixed costs like groceries (where we’ve seen inflation soar) and transportation, leaving little if anything behind after paying rent.

For most people who are living along the poverty line, it wouldn’t take much to disrupt the delicate balance of their stability. An unexpected health bill, a broken phone, an overdue payment — any of these things could tip the scales and lead to homelessness. And in a region with skyrocketing rents and stagnant support systems, more and more people are struggling to remain housed.

Housing

A shortage of available, affordable housing is directly correlated to rising homelessness numbers.

The current housing landscape can be attributed to a series of market and governmental decisions dating back to the 1980s and 1990s. A rapid decline in rental housing construction in the ’80s, followed by government cuts to social housing investments in the ’90s began to limit available housing options. Additional provincial cuts to social assistance also led to a rise in poverty, as monthly income amounts dropped by up to 20%. Chronic and long-term homelessness in Canada started to rise after these decisions.

Modern governments are beginning to make housing a greater priority, with the BC government committing $4.2 billion to housing over three years, but we can see that neglecting housing over decades has had a notable effect on homelessness.

What does homelessness do to the person experiencing it?

Being unhoused has deeply detrimental impacts, both mentally and physically. We must take these long-lasting impacts into account as we advocate for change.

Physical health struggles

When a person is experiencing homelessness, it leaves them exposed to the environment around them, including the weather and other physical dangers. Repeated exposure to the elements can lower a person’s immune system to the point that a simple cold to a housed person can be a serious illness for someone sleeping outdoors. People without homes are also in danger of weather-related illnesses like heat-stroke or hypothermia — and in extreme cases, death. Sleep deprivation can cause brain fog for people sleeping outdoors, and unhoused people often face the risk of having their possessions stolen while they sleep.

Mental health struggles

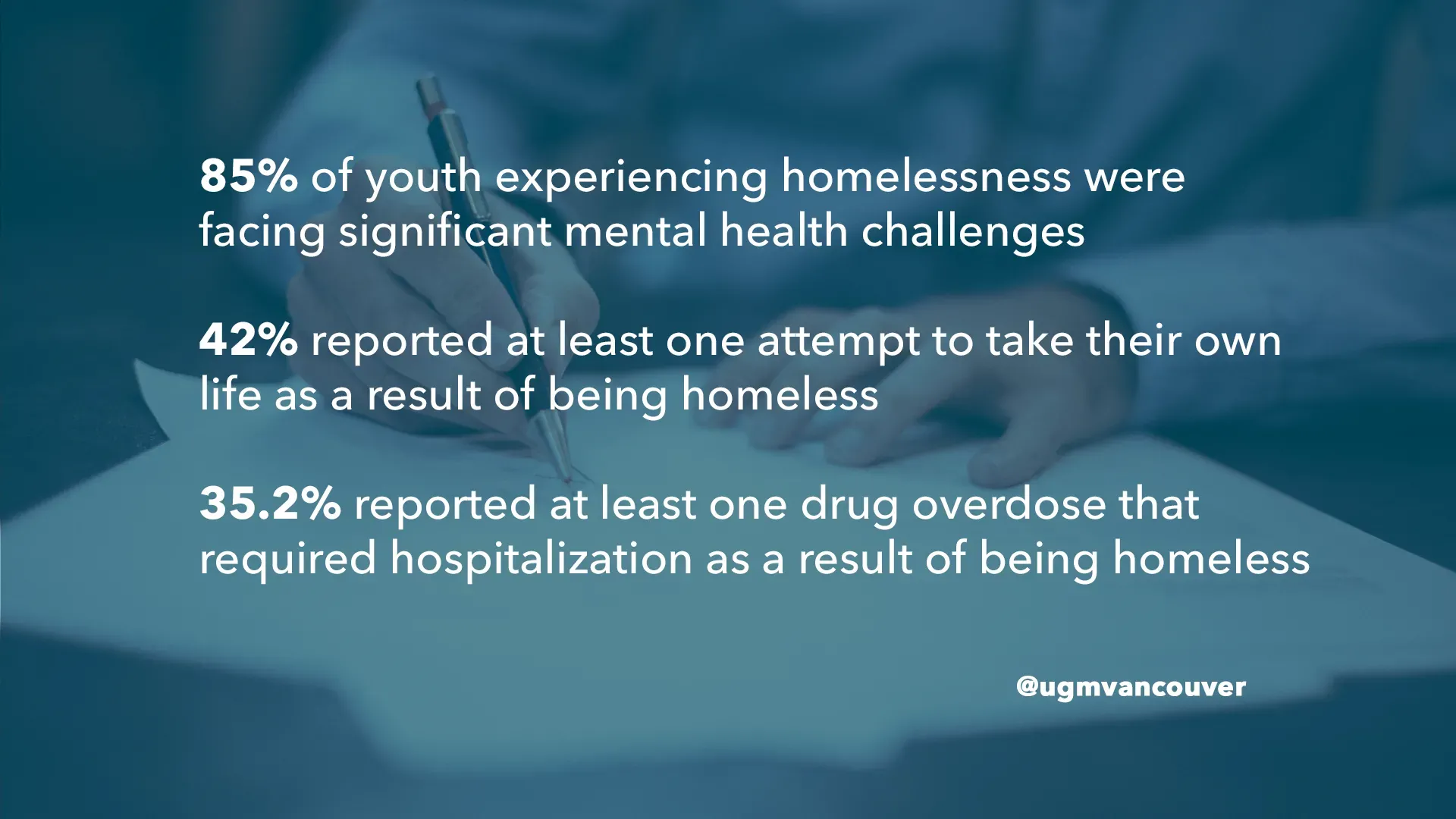

Between 30 and 35% of people who are homeless in Canada struggle with their mental health. In the 2023 Homeless Count in Greater Vancouver the number of people struggling is even more staggering at 53%. Mental health struggles can be a catch-22 for people experiencing homelessness: being unwell makes it difficult for people to keep their existing housing, and being without a home has a detrimental effect on mental health. For people experiencing severe mental illness, chronic homelessness can have an extremely harmful impact on their ability to seek support.

“I slept in shelters and on the street, hoping to outrun my depression. I was supposed to take care of everything, and I’d failed.” — Aurel, UGM Community Member

Homelessness can be demoralizing to a person’s mental health when they know they may have to face harsh environmental conditions. There’s also the added obstacle of the stigma attached to homelessness, as communities and legislators may assume common stereotypes like laziness instead of recognizing the surrounding reasons or issues that might lead a person into homelessness.

Read Aurel’s story to see the life-changing impact of safety and kindness.

Who is at risk of homelessness?

The truth is, everyone can be at risk of homelessness.

People can face homelessness through eviction, or by not being able to keep up with the cost of living and rent. People who are housed may need to increase their number of roommates or help an unhoused friend couchsurf while they search for an affordable apartment. Communities are changed when encampments spring up, and kids may struggle at school when they don’t know where they’ll be sleeping that night. Homelessness is not an individual problem, but a collective one.

It’s also not an isolated problem: homelessness is often built upon layers of disadvantage. In recent years, pensioners have returned from hospital stays to find they’ve lost their housing. Due to the current toxic drug crisis, many who are struggling with addiction and homelessness also have traumatic brain injuries from repeated overdoses. These compounding layers — of illness, of injustice — limit many people from finding their way to stable housing.

Because of my addiction, I couldn’t pay rent, and I lost my jobs. I ended up sleeping on the streets. For two months, I lived outside, and it was miserable — I was cold, wet, and hungry.” — Luis, UGM Community Member

Homelessness can happen to anyone because there simply aren’t enough homes. In Metro Vancouver, 47% of respondents in the 2023 Homeless Count shared they were experiencing homelessness because they were on a waitlist for housing.

Luis lost his apartment. Read his story of homecoming.

Who experiences homelessness the most?

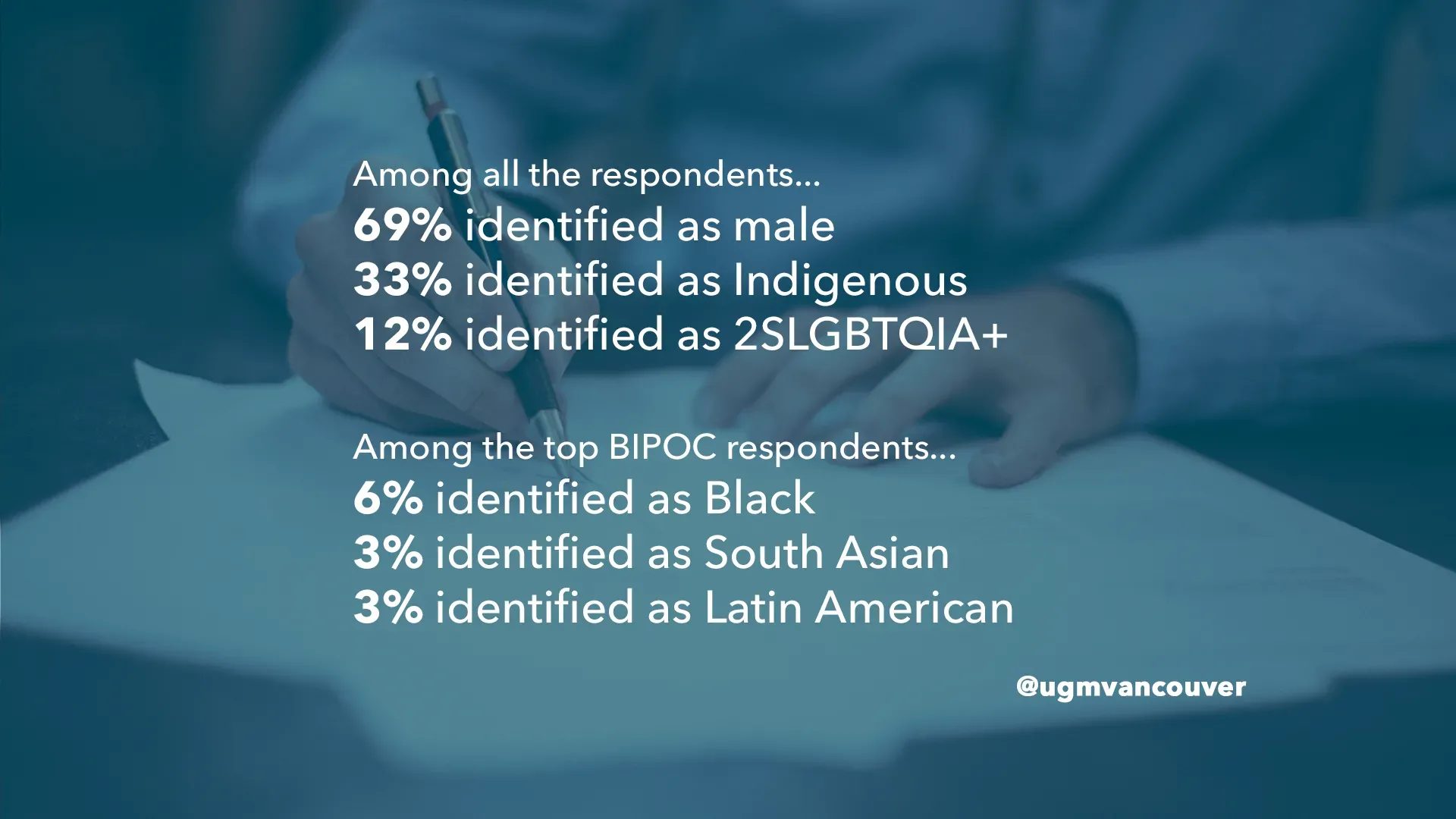

If we look at the results of the 2023 Homeless Count in Greater Vancouver, the people who experience homelessness the most are men, Indigenous, 2SLGBTQIA+, and other BIPOC community members.

Historically, homelessness has had a profound effect on Indigenous people as a symptom of colonialism. In the 2023 Homeless Count in Greater Vancouver, 64% of Indigenous people who self-identified as homeless cited lived or generational experience with residential schools.

How does homelessness affect families and children?

Homelessness has a detrimental cyclical effect on families and children. When their caretakers become homeless, children become homeless too, and that level of destabilization can be difficult to overcome. The stressors of poverty, conflict, relational breakdown, and uncertainty can cause children to struggle in school, experience negative physical and mental health outcomes, and develop behavioural issues as they age.

Of the people self-identifying as homeless in this year’s Homeless Count, 47% experienced homelessness for the first time in their youth. Thirty-one percent of respondents had lived in foster care or a youth group home. Statistics from a 2016 report show that:

The impacts of homelessness on young people are evident — and daunting.

There remains a lot of work to be done to keep families together and housed. Families stay in shelters twice as long as individuals, averaging 20 days compared to 10 days for the typical shelter user. Families face longer periods of disruption and uncertainty, and a longer road to stability and secure housing. And intergenerational trauma means that these stressors and experiences are likely to repeat.

Is homelessness getting worse in Metro Vancouver?

In a word: yes.

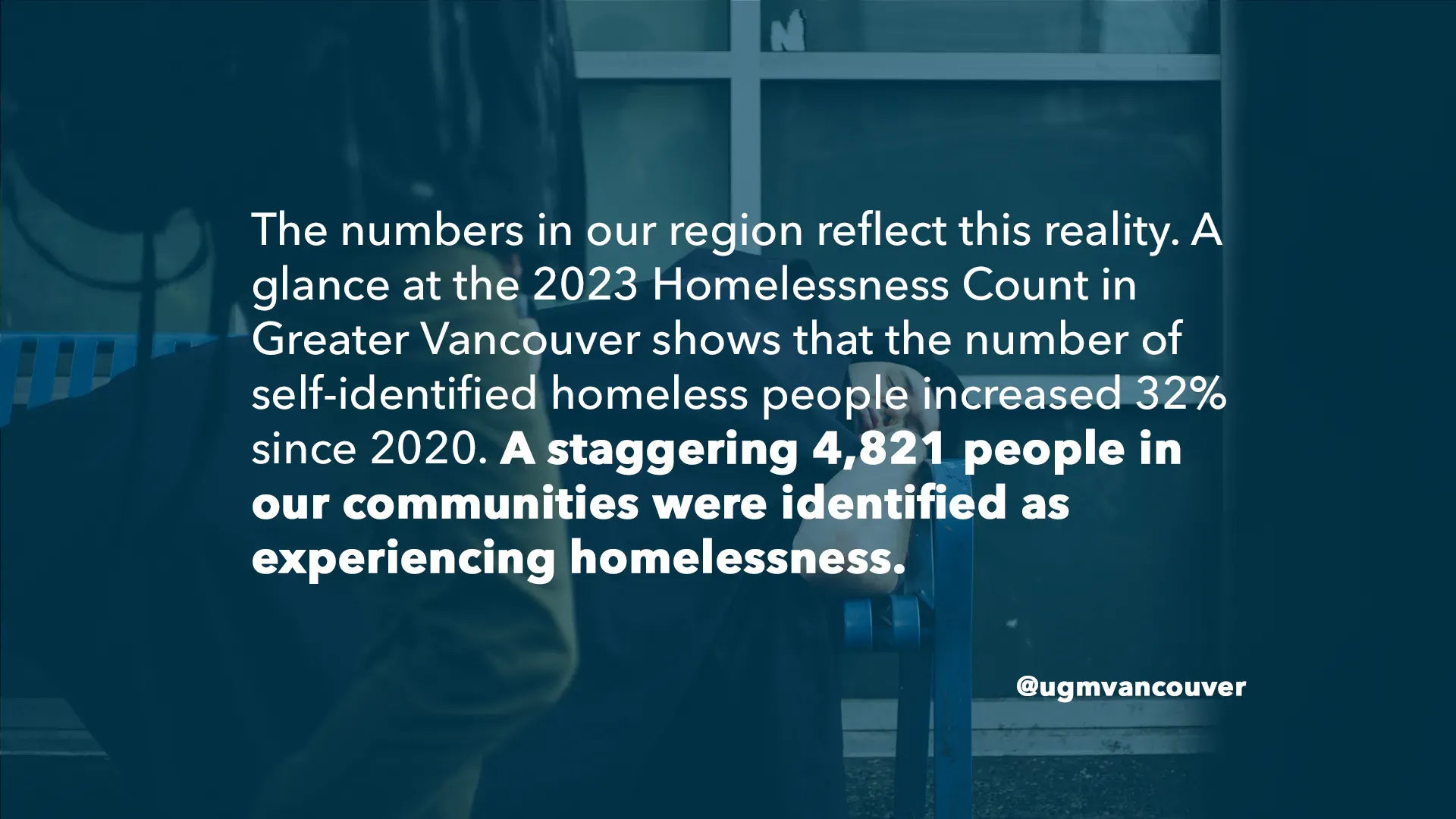

But let’s unpack this: an astounding increase in people experiencing homelessness across the region occurred between 2020 and 2023. If we look at the results of the 2023 Homeless Count in Greater Vancouver, the numbers show a 32% jump. The number of people unhoused also went up in every sub-region (Vancouver, Surrey, etc.) where the count was done. The COVID-19 pandemic was also a factor in the increase, with 15% of people surveyed identifying it as a reason for their homelessness.

Will homelessness ever end?

Ending homelessness is not a yes or no answer. There will always be people who become homeless through unforeseen circumstances like eviction, a lack of income, or unresolved trauma.

When we talk about “ending homelessness,” it’s not about simply making sure everyone is housed.

“The goal of ending homelessness is to ensure housing stability, which means people have a fixed address and housing that is appropriate (affordable, safe, adequately maintained, accessible and suitable in size), and includes required services as needed (supportive), in addition to income and supports.” – The Homeless Hub, cited in The Canadian Definition of Homelessness

What may be encouraging as we work to end homelessness is to look at the steps the federal and provincial governments have implemented over the years — and their plans for the future.

- In 2014, the federal government brought in the “Housing First” model to focus on housing people who are homeless right away. Previously, a person experiencing homelessness would need to seek treatment (i.e. sobriety) before accessing housing.

- The BC government is committing $1.5 billion in capital funding over three years to addressing homelessness, while the federal government has developed a homelessness strategy which includes a $2.2 billion investment to expand funding for people who are homeless.

Nonprofit organizations, too, have a role to play in helping people find housing. Whether it’s through building and maintaining supportive, transitional housing, or holding space for people who need assistance in putting together their housing applications, organizations like Union Gospel Mission can be a bridge to more stable living situations. Some of the organizations working to supply housing in Metro Vancouver include Lookout Housing + Health Society, Atira, PHS Community Services Society, RainCity Housing, Lu'ma Native Housing Society, and Whole Way House.

UGM helped me apply for housing, which felt like a pipe dream because of the housing crisis in BC. Six months later, I got a place. That was the happiest day of my life.” — Luis, UGM Community Member

The housing crisis underway in Metro Vancouver is not a small one. More people than ever before are without a safe, affordable address. But as communities support their neighbours and people advocate for change, we hope to see all levels of government taking seriously the human right to housing. Everyone, no matter their circumstances, is deserving of somewhere to live.

Sources and further reading:

- Canadian Definition of Homelessness

- Causes Of Homelessness

- October 2023 Rentals.ca Report

- DABC’s Response to 2023 BC Budget.

- Poverty | The Homeless Hub

- 2023 British Columbia - Food Banks Canada

- Consumer Price Index

- Mapping Homelessness Research in Canada

- Budget 2023 takes action on issues that matter most | BC Gov News

- 'I'm about to be homeless': Burnaby renters face evictions as new Metrotown towers proposed

- 2023 HOMELESS COUNT IN GREATER VANCOUVER

- Homelessness Statistics in Canada for 2023 - Made in CA

- What is a PiT Count? | The Homeless Hub

- What is Homelessness?

- Can we end homelessness?

- Homeless, impoverished at risk during B.C. heat wave, advocates warn | Vancouver Sun

- Extreme cold means 'it's life or death' for people living on Metro Vancouver streets

- Top Ten Health Issues Facing Homeless People

- How to Find Loved Ones in the Downtown Eastside | Union Gospel Mission

- How to Talk to Your Kids About Homelessness | Union Gospel Mission

- The State of Women's Housing Need & Homelessness in Canada: Key Findings

- Mental Health Care for Homeless Youth: A Demand for Action and Equity

- Mental Health - Covenant House Vancouver.

- Families with Children | The Homeless Hub